The Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park:

The Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park:

One of the Philippines’ Last Great Forests

One of the Philippines’ Last Great Forests

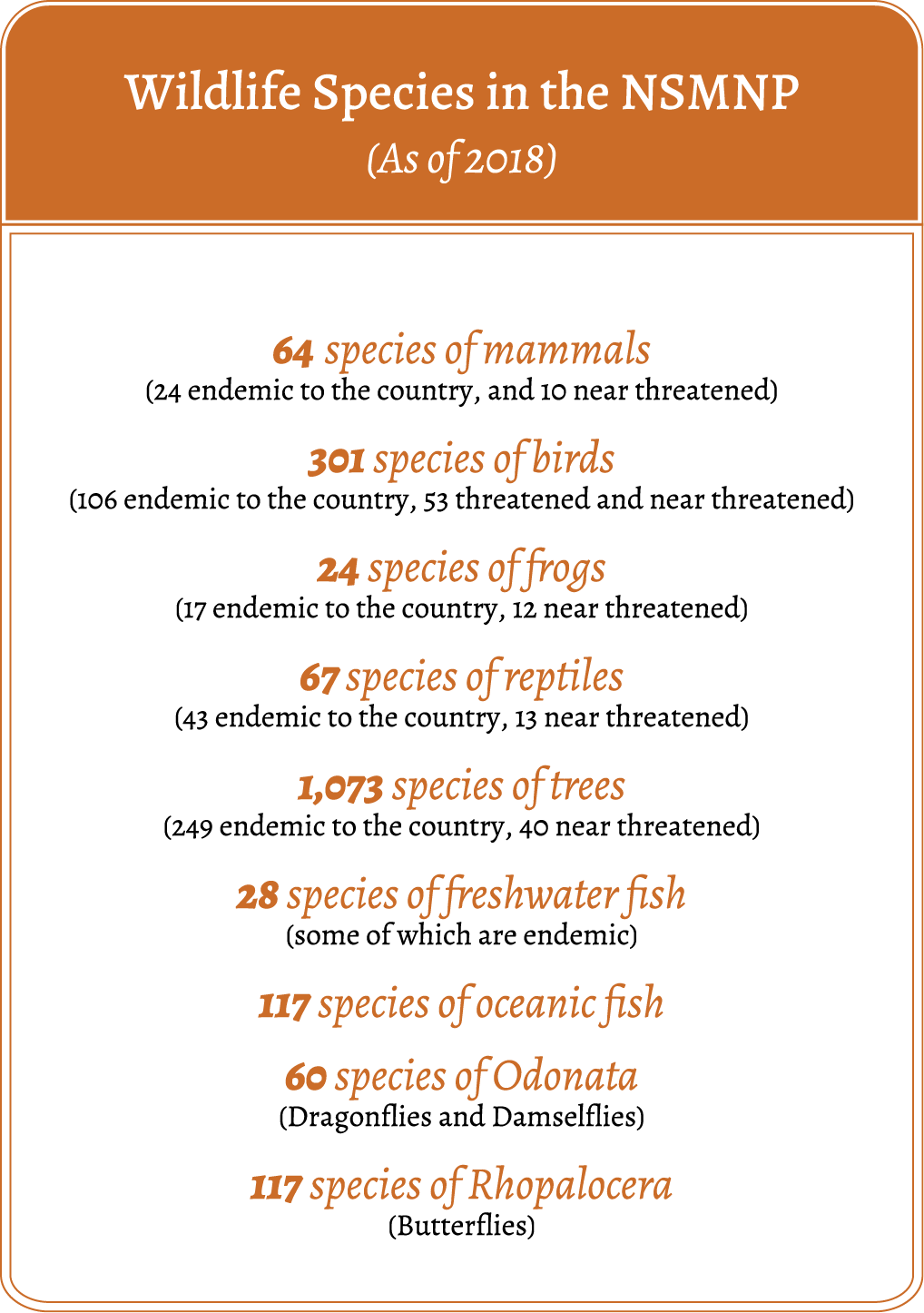

Known as the largest protected area in the Philippines, the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) boasts a wide range of ecosystems, serves as an ancestral domain to indigenous peoples, and includes an incredible number of endemic species.

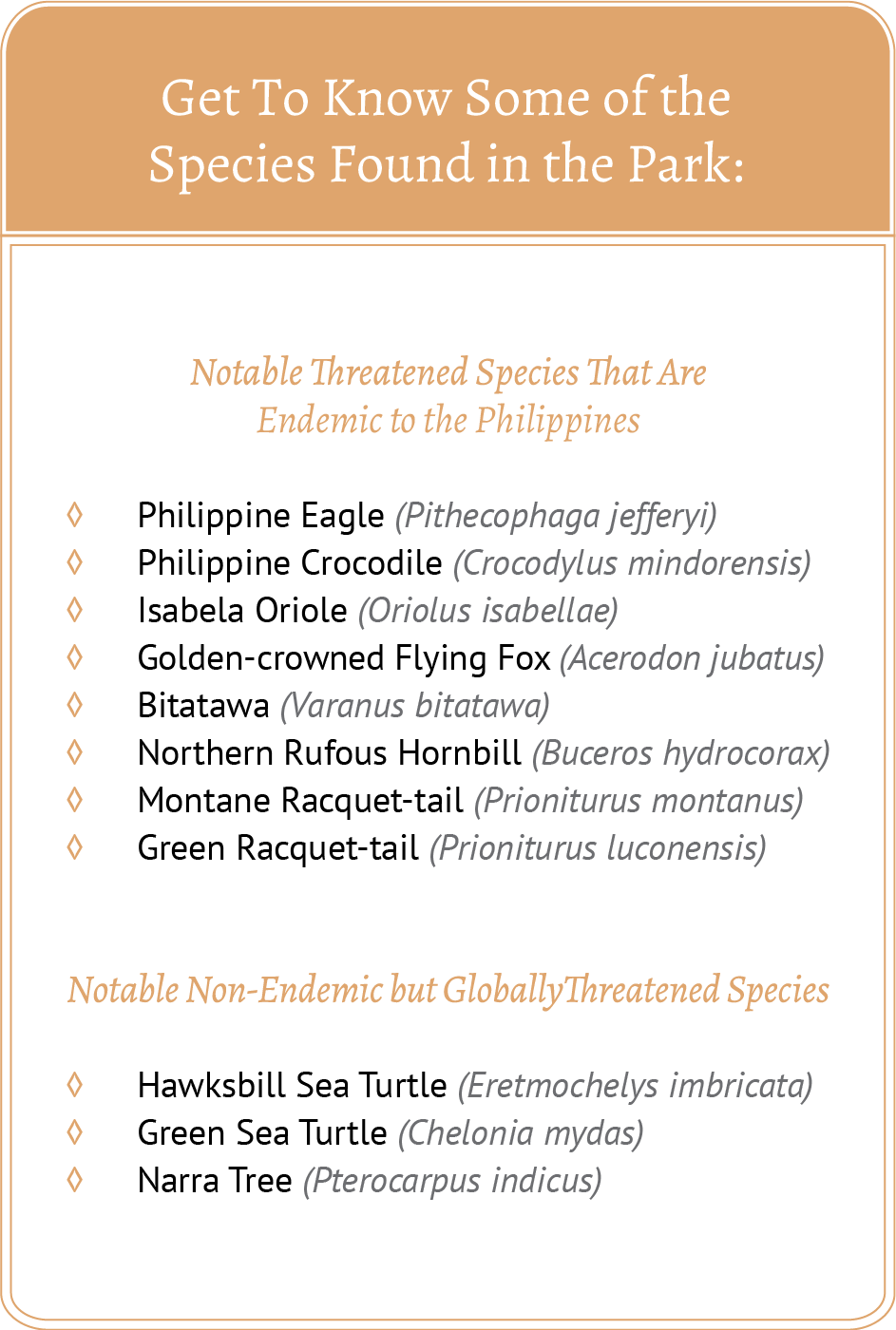

- The Park is one of the world’s 221 key sites for biodiversity conservation.

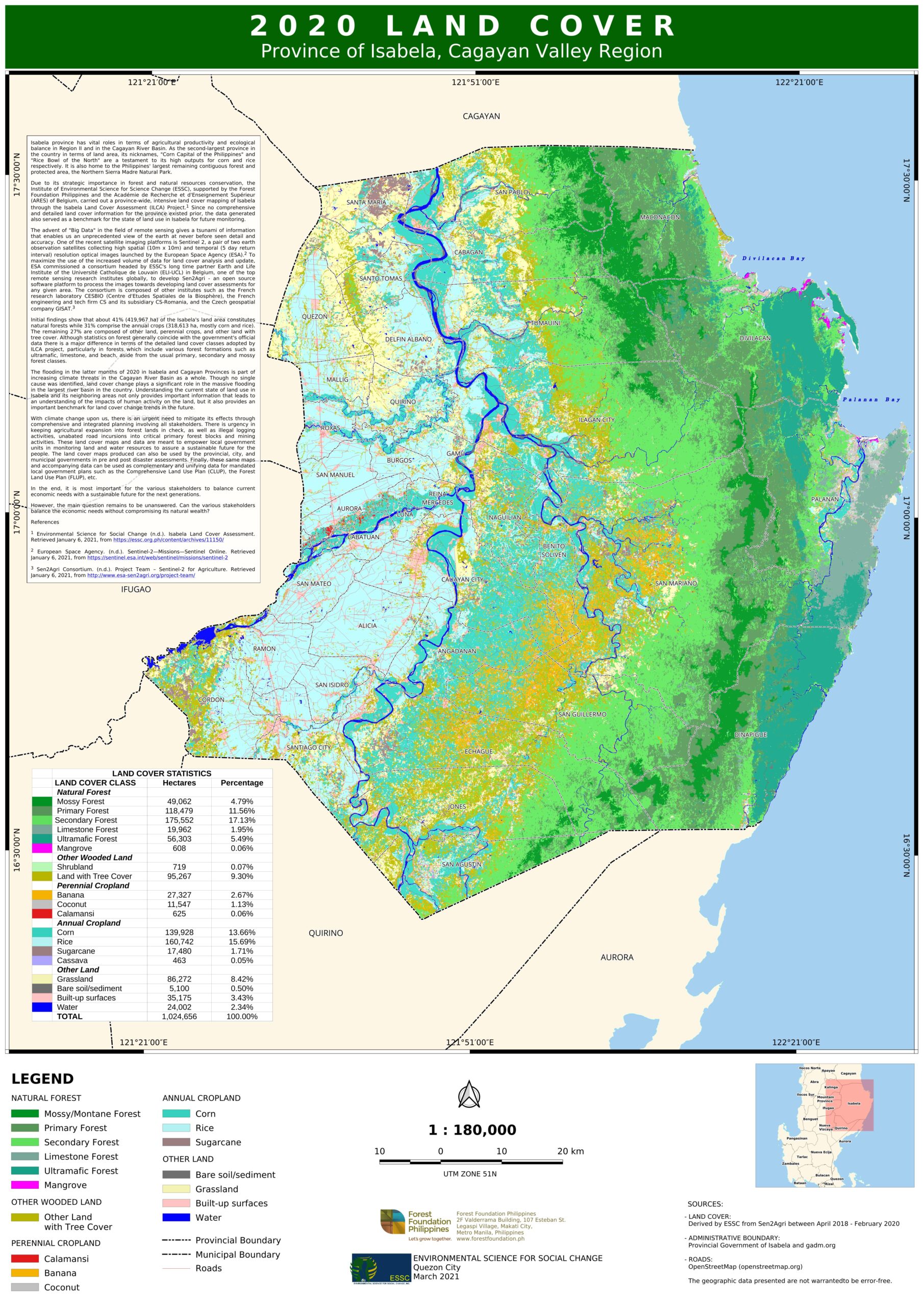

- It is the country’s largest protected forest, containing 118,479 hectares of its remaining primary forest.

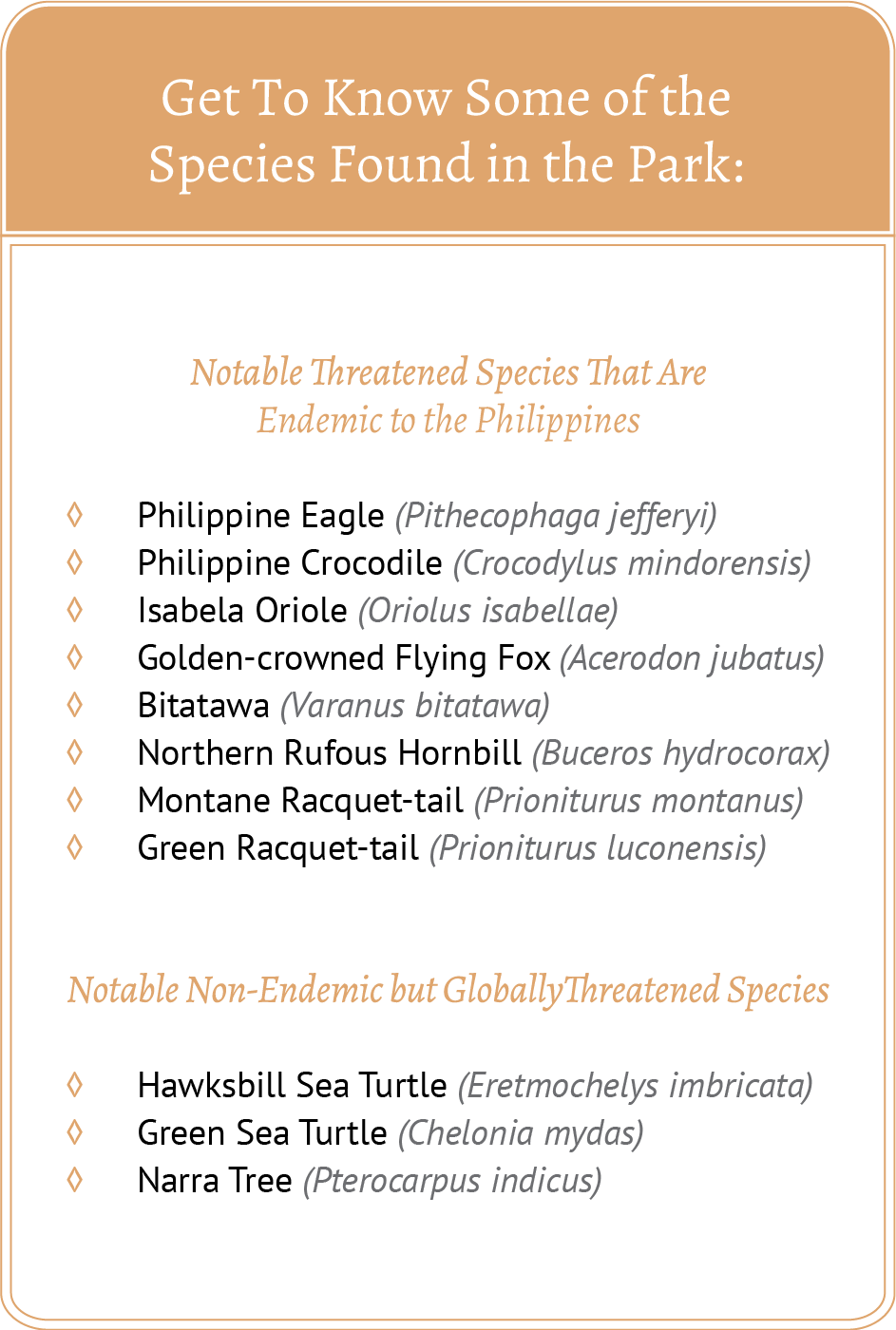

- 70 globally-threatened and near-threatened species make their homes in the Park.

- The NSMNP’s 12 major habitats show the diversity of its landscapes and coasts.

- Its ecosystems include lowland dipterocarp rainforest, limestone forest, ultrabasic forest, montane forest, mossy forest, marine waters, coral reefs, reef flats, seagrass beds, mangrove forest, beach, and beach forest on its coastal regions.

Where is the Northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range?

The Park is located in the eastern section of Isabela Province, within northeastern Luzon. It contains a middle section of the Northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range. Its coastal and marine areas cover 71,625 hectares while its habitats on land span 287,861 hectares. It is nestled within the municipalities of Palanan, Maconacon, and Divilacan and includes parts of San Mariano, Tumauini, Cabagan, San Pablo, Ilagan, and Dinapigue.

Where Are the Park’s Boundaries?

The Park has the following boundaries: the provincial boundary between Isabela and Cagayan in its north, the Disabungan River in its southern end, the Cagayan Valley in its west, and the Pacific Ocean in its eastern side.

When Was the Park Established?

All forest lands within a 45 kilometer radius from Palanan Point were declared part of the Palanan Wilderness Area through Presidential Letter of Instruction No. 917, published on August 22, 1979. The protected area around Palanan Point became part of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, which was established through the Republic Act 9125 or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park Act of 2001, adopted by the Senate and House of Representatives on April 22, 2001.

How did the Philippines lose much of its forest cover?

The NSMNP contains about 234,374 hectares of forest cover. In a country that has been subjected to commercial logging, these remaining forests are valuable now more than ever.

The beginning of the 1900s until the end of the century saw the decimation of the majority of the Philippines’ forest cover. The country’s lush forests spanned 21 million hectares in the early 1900s, and that number has since been hacked down to about 7.0 million hectares as of 2015.

Widespread logging is to blame for the most significant destruction brought on to our great forests. The American occupation of the Philippines brought with it large-scale logging that cut down the country’s forests to 17 million hectares during the Pacific War. The administration of Ferdinand Marcos also rapidly increased the country’s timber license agreements, raising them from 58 in 1969 to 471 in 1976. This decision led to the reduction of the country’s forests from 12 million hectares in the mid-1960s to 6.9 million hectares near the end of his presidency.

A study published by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in 2013 assessed the key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation. The study involved interviews and focus group discussions with key informants from General Nakar, Quezon; Southern Leyte; Palawan; and Mount Malindang. Key informants included members of government agencies, civil society organizations, LGUs, indigenous peoples, community members, and forest product traders. The researchers found that informants listed the following factors as key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation: 41% cited logging, 17% said kaingin is a key driver, and 13% pointed to biophysical factors such as climate change, typhoons, floods, landslides. Additionally 9% said that mining is another key driver and 8% pointed to charcoal making.

The loss of our forests through logging has brought cascading effects that are not easily addressed. For one thing, reduced forest cover results in biodiversity and habitat loss, threatening many of our country’s already vulnerable and endangered species. When lands are deforested, these are often converted to agricultural areas, which are more vulnerable to erosion and increased flooding. Moreover, because trees play a key role in the stability of watersheds, cutting down forests also reduces the flow of water that can be used for rice irrigation, lessening yields for rice and other crops.

Known as the largest protected area in the Philippines, the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) boasts a wide range of ecosystems, serves as an ancestral domain to indigenous peoples, and includes an incredible number of endemic species.

- The Park is one of the world’s 221 key sites for biodiversity conservation.

- It is the country’s largest protected forest, containing 118,479 hectares of its remaining primary forest.

- 70 globally-threatened and near-threatened species make their homes in the Park.

- The NSMNP’s 12 major habitats show the diversity of its landscapes and coasts.

- Its ecosystems include lowland dipterocarp rainforest, limestone forest, ultrabasic forest, montane forest, mossy forest, marine waters, coral reefs, reef flats, seagrass beds, mangrove forest, beach, and beach forest on its coastal regions.

Where is the Northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range?

The Park is located in the eastern section of Isabela Province, within northeastern Luzon. It contains a middle section of the Northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range. Its coastal and marine areas cover 71,625 hectares while its habitats on land span 287,861 hectares. It is nestled within the municipalities of Palanan, Maconacon, and Divilacan and includes parts of San Mariano, Tumauini, Cabagan, San Pablo, Ilagan, and Dinapigue.

Where Are the Park’s Boundaries?

The Park has the following boundaries: the provincial boundary between Isabela and Cagayan in its north, the Disabungan River in its southern end, the Cagayan Valley in its west, and the Pacific Ocean in its eastern side.

When Was the Park Established?

All forest lands within a 45 kilometer radius from Palanan Point were declared part of the Palanan Wilderness Area through Presidential Letter of Instruction No. 917, published on August 22, 1979. The protected area around Palanan Point became part of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, which was established through the Republic Act 9125 or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park Act of 2001, adopted by the Senate and House of Representatives on April 22, 2001.

How did the Philippines lose much of its forest cover?

The NSMNP contains about 234,374 hectares of forest cover. In a country that has been subjected to commercial logging, these remaining forests are valuable now more than ever.

The beginning of the 1900s until the end of the century saw the decimation of the majority of the Philippines’ forest cover. The country’s lush forests spanned 21 million hectares in the early 1900s, and that number has since been hacked down to about 7.0 million hectares as of 2015.

Widespread logging is to blame for the most significant destruction brought on to our great forests. The American occupation of the Philippines brought with it large-scale logging that cut down the country’s forests to 17 million hectares during the Pacific War. The administration of Ferdinand Marcos also rapidly increased the country’s timber license agreements, raising them from 58 in 1969 to 471 in 1976. This decision led to the reduction of the country’s forests from 12 million hectares in the mid-1960s to 6.9 million hectares near the end of his presidency.

A study published by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in 2013 assessed the key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation. The study involved interviews and focus group discussions with key informants from General Nakar, Quezon; Southern Leyte; Palawan; and Mount Malindang. Key informants included members of government agencies, civil society organizations, LGUs, indigenous peoples, community members, and forest product traders. The researchers found that informants listed the following factors as key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation: 41% cited logging, 17% said kaingin is a key driver, and 13% pointed to biophysical factors such as climate change, typhoons, floods, landslides. Additionally 9% said that mining is another key driver and 8% pointed to charcoal making.

The loss of our forests through logging has brought cascading effects that are not easily addressed. For one thing, reduced forest cover results in biodiversity and habitat loss, threatening many of our country’s already vulnerable and endangered species. When lands are deforested, these are often converted to agricultural areas, which are more vulnerable to erosion and increased flooding. Moreover, because trees play a key role in the stability of watersheds, cutting down forests also reduces the flow of water that can be used for rice irrigation, lessening yields for rice and other crops.

Ecosystem Services Provided by the NSMNP

Shield to Typhoons

Each year, the Philippines is battered by multiple typhoons, which cause massive damage to homes, infrastructure, and agriculture. When storms strike, the Sierra Madre Mountain Range is there to act as a barrier that buffers the speed of tropical cyclones. The Sierra Madre serves as effective protection against typhoons because of the height of its mountains, thus shielding the country from storms that sweep into eastern Luzon after passing the Pacific Ocean. These mountains slow down storms, providing meteorologists and disaster risk reduction agencies with more time to plan evacuations. While only a section of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range is part of the NSMNP, it is pertinent for us to protect every part of these mountains.

Water Source

When it rains, the thick vegetation, leaf litter, and soil of the NSMNP soak up water like a sponge, making the Northern Sierra Madre area an abundant source of water. In fact, it is a major water source for Region 2, funneling water for both irrigation and household needs. Good irrigation allows crop production to thrive. In 1992, Regions 2 and 3 contained 50% of the country’s irrigated farmlands and produced 30% of its palay in that year.

Ecosystem Services Provided by the NSMNP

Shield to Typhoons

Each year, the Philippines is battered by multiple typhoons, which cause massive damage to homes, infrastructure, and agriculture. When storms strike, the Sierra Madre Mountain Range is there to act as a barrier that buffers the speed of tropical cyclones. The Sierra Madre serves as effective protection against typhoons because of the height of its mountains, thus shielding the country from storms that sweep into eastern Luzon after passing the Pacific Ocean. These mountains slow down storms, providing meteorologists and disaster risk reduction agencies with more time to plan evacuations. While only a section of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range is part of the NSMNP, it is pertinent for us to protect every part of these mountains.

Water Source

When it rains, the thick vegetation, leaf litter, and soil of the NSMNP soak up water like a sponge, making the Northern Sierra Madre area an abundant source of water. In fact, it is a major water source for Region 2, funneling water for both irrigation and household needs. Good irrigation allows crop production to thrive. In 1992, Regions 2 and 3 contained 50% of the country’s irrigated farmlands and produced 30% of its palay in that year.

A Home for Life

The sprawling forests, coastal areas, and stretches of mountain contained in the NSMNP are full of a variety of ecosystems and wildlife species. Many of these are endemic to the Philippines, Luzon, and the Northern Sierra Madre—meaning they cannot be found nowhere else in the world. These lands are also home to indigenous peoples and are considered the ancestral domains of the Agtas and Dumagats.

The indigenous peoples and other residents of the Park.

- Many current residents of the Park were workers of logging companies based in the Park in the 1960s or 1970s as well as their descendants.

A Home for Life

The sprawling forests, coastal areas, and stretches of mountain contained in the NSMNP are full of a variety of ecosystems and wildlife species. Many of these are endemic to the Philippines, Luzon, and the Northern Sierra Madre—meaning they cannot be found nowhere else in the world. These lands are also home to indigenous peoples and are considered the ancestral domains of the Agtas and Dumagats.

The indigenous peoples and other residents of the Park.

- Many current residents of the Park were workers of logging companies based in the Park in the 1960s or 1970s as well as their descendants.

Threats to the Sierra Madre Natural Park

Timber Poaching

Commercial logging operations are prohibited within the NSMNP. However, small-scale timber poaching activities still abound in the Park. This timber is used for local or domestic needs of communities and infrastructure projects. There have been on and off apprehensions across the years, and the DENR’s Lawin monitoring system helps to reduce these activities.

Timber Poaching

Commercial logging operations are prohibited within the NSMNP. However, small-scale timber poaching activities still abound in the Park. This timber is used for local or domestic needs of communities and infrastructure projects. There have been on and off apprehensions across the years, and the DENR’s Lawin monitoring system helps to reduce these activities.

Infrastructure

The Ilagan-Divilacan road has already been constructed, while a road from San Mariano to Palanan is being developed.

All types of major infrastructure within the Park can cause habitat loss, degrade biodiversity, and reduce forest cover. Built roads make it easier to travel across the Park and encourage people to reside on both sides of it. Migrants who settle next to these infrastructures eventually expand their activities and alter the Park’s landscape. Within the Park, there is a road that runs from Ilagan to Divilacan and the impacts of its construction must be mitigated. Another road from San Mariano to Palanan is being constructed, but progress has been halted due to a lack of permits and clearances. An airport construction was initiated in Dipudo, Divilacan but was discontinued.

Infrastructure

The Ilagan-Divilacan road has already been constructed, while a road from San Mariano to Palanan is being developed.

All types of major infrastructure within the Park can cause habitat loss, degrade biodiversity, and reduce forest cover. Built roads make it easier to travel across the Park and encourage people to reside on both sides of it. Migrants who settle next to these infrastructures eventually expand their activities and alter the Park’s landscape. Within the Park, there is a road that runs from Ilagan to Divilacan and the impacts of its construction must be mitigated. Another road from San Mariano to Palanan is being constructed, but progress has been halted due to a lack of permits and clearances. An airport construction was initiated in Dipudo, Divilacan but was discontinued.

Threats to the quality of life of indigenous peoples

Over 1,000 Agta or Dumagat live within the NSMNP.

While the Agta or Dumagat indigenous peoples who live in the Park are part of the Protected Area Management Board, their quality of life can still be greatly improved. They support their basic needs through livelihoods such as gathering, fishing, farming, hunting, trading forest products, and seasonal labor. Despite their usufruct and settlement rights in the Park, they are not the legal owners of their land. The Agta have struggled to gain legal ownership of their land in the NSMNP under the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 for decades due to factors such as conflict and institutional competition. This makes them vulnerable to losing their land in areas with infrastructure developments.

Threats to the quality of life of indigenous peoples

Over 1,000 Agta or Dumagat live within the NSMNP.

While the Agta or Dumagat indigenous peoples who live in the Park are part of the Protected Area Management Board, their quality of life can still be greatly improved. They support their basic needs through livelihoods such as gathering, fishing, farming, hunting, trading forest products, and seasonal labor. Despite their usufruct and settlement rights in the Park, they are not the legal owners of their land. The Agta have struggled to gain legal ownership of their land in the NSMNP under the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 for decades due to factors such as conflict and institutional competition. This makes them vulnerable to losing their land in areas with infrastructure developments.

Migration

Migration is another possible source of conflict for IPs in the Park, since this can put strain on the natural resources they depend on. When people move into the Park, this can also increase activities such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) and the building of settlements. A 1990 study done in the Philippines for the ASEAN Economic Bulletin showed that migration to uplands also brings an increased amount of unsustainable farming practices, promoting deforestation. It also recommended providing land tenure and subsidizing conservation practices to prevent further deforestation.

Migration

Migration is another possible source of conflict for IPs in the Park, since this can put strain on the natural resources they depend on. When people move into the Park, this can also increase activities such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) and the building of settlements. A 1990 study done in the Philippines for the ASEAN Economic Bulletin showed that migration to uplands also brings an increased amount of unsustainable farming practices, promoting deforestation. It also recommended providing land tenure and subsidizing conservation practices to prevent further deforestation.

Biodiversity Loss

One of the biggest threats faced by wildlife in the NSMNP is habitat loss. When infrastructure like roads are built, construction clears away forests and brings more traffic and human activity. Harmful agricultural practices such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) can also threaten habitats. Other threats to biodiversity include illegal hunting and fishing activities. Residents of the Park are allowed to sustainably hunt and fish to fulfill their basic needs, but problems arise when outsiders engage in illegal hunting and fishing activities.

Biodiversity Loss

One of the biggest threats faced by wildlife in the NSMNP is habitat loss. When infrastructure like roads are built, construction clears away forests and brings more traffic and human activity. Harmful agricultural practices such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) can also threaten habitats. Other threats to biodiversity include illegal hunting and fishing activities. Residents of the Park are allowed to sustainably hunt and fish to fulfill their basic needs, but problems arise when outsiders engage in illegal hunting and fishing activities.

Threats to the Sierra Madre Natural Park

Timber Poaching

Commercial logging operations are prohibited within the NSMNP. However, small-scale timber poaching activities still abound in the Park. This timber is used for local or domestic needs of communities and infrastructure projects. There have been on and off apprehensions across the years, and the DENR’s Lawin monitoring system helps to reduce these activities.

Timber Poaching

Commercial logging operations are prohibited within the NSMNP. However, small-scale timber poaching activities still abound in the Park. This timber is used for local or domestic needs of communities and infrastructure projects. There have been on and off apprehensions across the years, and the DENR’s Lawin monitoring system helps to reduce these activities.

Infrastructure

The Ilagan-Divilacan road has already been constructed, while a road from San Mariano to Palanan is being developed.

All types of major infrastructure within the Park can cause habitat loss, degrade biodiversity, and reduce forest cover. Built roads make it easier to travel across the Park and encourage people to reside on both sides of it. Migrants who settle next to these infrastructures eventually expand their activities and alter the Park’s landscape. Within the Park, there is a road that runs from Ilagan to Divilacan and the impacts of its construction must be mitigated. Another road from San Mariano to Palanan is being constructed, but progress has been halted due to a lack of permits and clearances. An airport construction was initiated in Dipudo, Divilacan but was discontinued.

Infrastructure

The Ilagan-Divilacan road has already been constructed, while a road from San Mariano to Palanan is being developed.

All types of major infrastructure within the Park can cause habitat loss, degrade biodiversity, and reduce forest cover. Built roads make it easier to travel across the Park and encourage people to reside on both sides of it. Migrants who settle next to these infrastructures eventually expand their activities and alter the Park’s landscape. Within the Park, there is a road that runs from Ilagan to Divilacan and the impacts of its construction must be mitigated. Another road from San Mariano to Palanan is being constructed, but progress has been halted due to a lack of permits and clearances. An airport construction was initiated in Dipudo, Divilacan but was discontinued.

Threats to the quality of life of indigenous peoples

Over 1,000 Agta or Dumagat live within the NSMNP.

While the Agta or Dumagat indigenous peoples who live in the Park are part of the Protected Area Management Board, their quality of life can still be greatly improved. They support their basic needs through livelihoods such as gathering, fishing, farming, hunting, trading forest products, and seasonal labor. Despite their usufruct and settlement rights in the Park, they are not the legal owners of their land. The Agta have struggled to gain legal ownership of their land in the NSMNP under the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 for decades due to factors such as conflict and institutional competition. This makes them vulnerable to losing their land in areas with infrastructure developments.

Threats to the quality of life of indigenous peoples

Over 1,000 Agta or Dumagat live within the NSMNP.

While the Agta or Dumagat indigenous peoples who live in the Park are part of the Protected Area Management Board, their quality of life can still be greatly improved. They support their basic needs through livelihoods such as gathering, fishing, farming, hunting, trading forest products, and seasonal labor. Despite their usufruct and settlement rights in the Park, they are not the legal owners of their land. The Agta have struggled to gain legal ownership of their land in the NSMNP under the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act of 1997 for decades due to factors such as conflict and institutional competition. This makes them vulnerable to losing their land in areas with infrastructure developments.

Migration

Migration is another possible source of conflict for IPs in the Park, since this can put strain on the natural resources they depend on. When people move into the Park, this can also increase activities such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) and the building of settlements. A 1990 study done in the Philippines for the ASEAN Economic Bulletin showed that migration to uplands also brings an increased amount of unsustainable farming practices, promoting deforestation. It also recommended providing land tenure and subsidizing conservation practices to prevent further deforestation.

Migration

Migration is another possible source of conflict for IPs in the Park, since this can put strain on the natural resources they depend on. When people move into the Park, this can also increase activities such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) and the building of settlements. A 1990 study done in the Philippines for the ASEAN Economic Bulletin showed that migration to uplands also brings an increased amount of unsustainable farming practices, promoting deforestation. It also recommended providing land tenure and subsidizing conservation practices to prevent further deforestation.

Biodiversity Loss

One of the biggest threats faced by wildlife in the NSMNP is habitat loss. When infrastructure like roads are built, construction clears away forests and brings more traffic and human activity. Harmful agricultural practices such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) can also threaten habitats. Other threats to biodiversity include illegal hunting and fishing activities. Residents of the Park are allowed to sustainably hunt and fish to fulfill their basic needs, but problems arise when outsiders engage in illegal hunting and fishing activities.

Biodiversity Loss

One of the biggest threats faced by wildlife in the NSMNP is habitat loss. When infrastructure like roads are built, construction clears away forests and brings more traffic and human activity. Harmful agricultural practices such as kaingin (slash and burn farming) can also threaten habitats. Other threats to biodiversity include illegal hunting and fishing activities. Residents of the Park are allowed to sustainably hunt and fish to fulfill their basic needs, but problems arise when outsiders engage in illegal hunting and fishing activities.

Conservation and Management

The NSMNP Act of 2001

Signed on April 22, 2001, Republic Act 9125 or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park Act of 2001 declared the NSMNP as a protected area, classifying it as a natural park under the National Integrated Protected Areas System. Notably, the Act defined the Park’s boundaries and buffer zones.

Key policies in the Act detailed provisions about the Park’s management, management plan, zoning, resources and facilities, prohibited activities, funding, tenured migrants, and the recognition of ancestral lands and domains.

The Act also required the establishment of the Park’s Protected Area Management Board (PAMB), granting it the mandate to create policies and provide permits for activities within the Park and its buffer zones. Lorenzo stated that the PAMB has continued to monitor the Park through committees that oversee its protection. It also grants researchers permission to conduct studies within the NSMNP.

Aside from establishing a PAMB, the Act also declared that the Park should have an Office of the Protected Area Superintendent (PASu). The PASu is the chief Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) officer that handles the Park and its buffer zones, charged with protecting the Park’s natural resources.

Araño observed that RA 9125 finally further deterred illegal poachers and financers, enhancing the Park’s biodiversity protection.

Protected Area Management Plan

One of the biggest accomplishments of the Protected Area Management Plan was the creation of management zones, defining the land use of different areas and delineating sections of land for multiple use, strict protection, and so on. Araño added that before this was established, zoning was negotiated among residents of the park.

Lorenzo explained that the plan was implemented from 2019 to 2023, and it is due for updating in 2023. He added that only 40% of the ambitious plan was implemented due to too few personnel and a lack of adequate funding.

Now that the PASu is formulating a new 5-year management plan, Lorenzo said that his office plans to take on a lean and mean approach that integrates existing protection and conservation efforts that are funded by the General Appropriations Act. It will receive approximately PHP 5 billion in funding.

Conservation and Management

The NSMNP Act of 2001

Signed on April 22, 2001, Republic Act 9125 or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park Act of 2001 declared the NSMNP as a protected area, classifying it as a natural park under the National Integrated Protected Areas System. Notably, the Act defined the Park’s boundaries and buffer zones.

Key policies in the Act detailed provisions about the Park’s management, management plan, zoning, resources and facilities, prohibited activities, funding, tenured migrants, and the recognition of ancestral lands and domains.

The Act also required the establishment of the Park’s Protected Area Management Board (PAMB), granting it the mandate to create policies and provide permits for activities within the Park and its buffer zones. Lorenzo stated that the PAMB has continued to monitor the Park through committees that oversee its protection. It also grants researchers permission to conduct studies within the NSMNP.

Aside from establishing a PAMB, the Act also declared that the Park should have an Office of the Protected Area Superintendent (PASu). The PASu is the chief Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) officer that handles the Park and its buffer zones, charged with protecting the Park’s natural resources.

Araño observed that RA 9125 finally further deterred illegal poachers and financers, enhancing the Park’s biodiversity protection.

Protected Area Management Plan

One of the biggest accomplishments of the Protected Area Management Plan was the creation of management zones, defining the land use of different areas and delineating sections of land for multiple use, strict protection, and so on. Araño added that before this was established, zoning was negotiated among residents of the park.

Lorenzo explained that the plan was implemented from 2019 to 2023, and it is due for updating in 2023. He added that only 40% of the ambitious plan was implemented due to too few personnel and a lack of adequate funding.

Now that the PASu is formulating a new 5-year management plan, Lorenzo said that his office plans to take on a lean and mean approach that integrates existing protection and conservation efforts that are funded by the General Appropriations Act. It will receive approximately PHP 5 billion in funding.

NIPAS Act and E-NIPAS Act

The National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992, also known as Republic Act 7586, is commonly referred to as the “Bible” for conserving protected areas in the Philippines, according to Lorenzo. It is supplemented by the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018 or Republic Act 11038.

For Lorenzo, the implementation of the E-NIPAS Act has enhanced the conservation of protected areas in the Philippines. Since the NSMNP lacks its own rules and regulations, these are anchored in the E-NIPAS. The E-NIPAS also expanded PAMB membership from 38 to 67. At present, the PAMB includes members of the Department of Agriculture, the National Economic and Development Authority, the Department of Science and Technology, the Philippine National Police, and the Department of National Defense. The expanded membership provides a broader, multi-stakeholder perspective on the DENR’s conservation efforts.

B+WISER: Transforming Forest Protection

The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience or B+WISER Program was a joint endeavor of DENR and USAID from 2012 to 2018—the Program aimed to conserve the biodiversity of vulnerable areas through practical, science-based, and community-based strategies.

NSMNP is among the B+WISER target forest areas and has worked with communities in Maconacon, Divilican, Palanan, Dinapigue, San Mariano, Ilagan, Tumauini, Cabagan, and San Pablo.

Some of the Program’s milestones concerning NSMNP were the comprehensive Baseline Vulnerability Assessment of the Park and the launching of the LAWIN Forest and Biodiversity Protection System as a national forest and biodiversity protection strategy. In 2015, B+WISER began developing and pilot-testing the LAWIN System in protected areas, and it was adopted in 2018 through DENR-DAO 2018-21.

NIPAS Act and E-NIPAS Act

The National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992, also known as Republic Act 7586, is commonly referred to as the “Bible” for conserving protected areas in the Philippines, according to Lorenzo. It is supplemented by the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018 or Republic Act 11038.

For Lorenzo, the implementation of the E-NIPAS Act has enhanced the conservation of protected areas in the Philippines. Since the NSMNP lacks its own rules and regulations, these are anchored in the E-NIPAS. The E-NIPAS also expanded PAMB membership from 38 to 67. At present, the PAMB includes members of the Department of Agriculture, the National Economic and Development Authority, the Department of Science and Technology, the Philippine National Police, and the Department of National Defense. The expanded membership provides a broader, multi-stakeholder perspective on the DENR’s conservation efforts.

B+WISER: Transforming Forest Protection

The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience or B+WISER Program was a joint endeavor of DENR and USAID from 2012 to 2018—the Program aimed to conserve the biodiversity of vulnerable areas through practical, science-based, and community-based strategies.

NSMNP is among the B+WISER target forest areas and has worked with communities in Maconacon, Divilican, Palanan, Dinapigue, San Mariano, Ilagan, Tumauini, Cabagan, and San Pablo.

Some of the Program’s milestones concerning NSMNP were the comprehensive Baseline Vulnerability Assessment of the Park and the launching of the LAWIN Forest and Biodiversity Protection System as a national forest and biodiversity protection strategy. In 2015, B+WISER began developing and pilot-testing the LAWIN System in protected areas, and it was adopted in 2018 through DENR-DAO 2018-21.

LAWIN Forest and Biodiversity Protection System

A system made for protecting forests and biodiversity, the DENR’s LAWIN uses open-source technology to monitor natural forests and forest areas covered by B+WISER such as the NSMNP.

Patrollers use a smartphone app to electronically record and analyze data on prohibited activities, forest conditions, and wildlife. Records made by patrollers can also be geotagged. This data allows people in charge to make better decisions when faced with these threats. The app can also create maps showing the spatial distribution of observations made by patrollers.

The use of LAWIN is not without its challenges. Aside from needing more manpower, Araño explained that one challenge faced by the DENR in implementing LAWIN is the need to increase patrol time.

Local Knowledge of Flora

Although they may be given less attention, conserving the flora of the Park is equally important. From 1999 to 2000, Garcia and Acay Jr. conducted an ethnobotany study of Agta communities to understand how they utilize resources within the NSMNP.

The researchers observed at least 301 plants, all valuable to the Agta for creating medicine, building houses, agriculture practices, producing handicrafts sold in the market, cooking and food preparation, fabricating traditional instruments or devices, hunting and fishing activities, and many other needs. They are tied to the Park flora and have a rich knowledge.

A long-term forest research site was also established inside the NSMNP. Initiated in 1994 by the late Leonard Co, the Palanan Plot is a 16-hectare field laboratory for the study of Philippine forest dynamics and biodiversity. 325 species of trees are found inside the plot as of 2016 census. Long-term studies inside the plot revealed how forests respond to continuous disturbances. This data was used to determine typhoon resilient and resistant tree species and what the ideal habitats of these species are.

As an underrepresented sector, conducting more studies such as this can influence future policies and programs about the NSMNP. This would equip relevant stakeholders with strategies to conserve the resources found in the Park – potentially carving more space for their voices to be heard.

LAWIN Forest and Biodiversity Protection System

A system made for protecting forests and biodiversity, the DENR’s LAWIN uses open-source technology to monitor natural forests and forest areas covered by B+WISER such as the NSMNP.

Patrollers use a smartphone app to electronically record and analyze data on prohibited activities, forest conditions, and wildlife. Records made by patrollers can also be geotagged. This data allows people in charge to make better decisions when faced with these threats. The app can also create maps showing the spatial distribution of observations made by patrollers.

The use of LAWIN is not without its challenges. Aside from needing more manpower, Araño explained that one challenge faced by the DENR in implementing LAWIN is the need to increase patrol time.

Local Knowledge of Flora

Although they may be given less attention, conserving the flora of the Park is equally important. From 1999 to 2000, Garcia and Acay Jr. conducted an ethnobotany study of Agta communities to understand how they utilize resources within the NSMNP.

The researchers observed at least 301 plants, all valuable to the Agta for creating medicine, building houses, agriculture practices, producing handicrafts sold in the market, cooking and food preparation, fabricating traditional instruments or devices, hunting and fishing activities, and many other needs. They are tied to the Park flora and have a rich knowledge.

A long-term forest research site was also established inside the NSMNP. Initiated in 1994 by the late Leonard Co, the Palanan Plot is a 16-hectare field laboratory for the study of Philippine forest dynamics and biodiversity. 325 species of trees are found inside the plot as of 2016 census. Long-term studies inside the plot revealed how forests respond to continuous disturbances. This data was used to determine typhoon resilient and resistant tree species and what the ideal habitats of these species are.

As an underrepresented sector, conducting more studies such as this can influence future policies and programs about the NSMNP. This would equip relevant stakeholders with strategies to conserve the resources found in the Park – potentially carving more space for their voices to be heard.

Saving the Philippine Crocodile

The Mabuwaya Foundation located in Cabagan, Isabela, was established in 2003 to save one of the rarest species in the world: the endemic, freshwater Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis), as well as the saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) found in the same region It was on the brink of extinction in the 1990s, with negative ideas such as “corruption” associated with them.

Mabuwaya successfully applied its holistic conservation program. The local crocodile population grew from less than 20 to around 100. The wild population of crocodiles in the Park is still increasing. The program encompasses five components that empower communities and protect other critical species in the Park.

Communication, Education, and Public Awareness (CEPA) Campaigns focus on involving and organizing youth groups to educate them on the biodiversity of Sierra Madre. They work closely with the development communications students from Isabela State University (ISU) to conduct puppet shows, field visits, school lectures, and CEPA materials like posters, flyers, and a children’s book.

The research component mainly comprises biological, ecological, and telemetry studies of crocodiles to learn more about their characteristics, interactions within their environment, and where they gather in the NSMNP. Mabuwaya works with other institutions like ISU, the University of the Philippines Diliman, Los Baños, and Baguio, and the Netherlands University to produce even anthropological research within the Park.

Protection was born from the need to equip locals, including indigenous people, with the skills to participate effectively in community-based conservation. Mabuwaya’s COO, Marites Gatan-Balbas, and Director Merlijn van Weerd are training twelve sanctuary guards to manage the crocodile sanctuaries in San Mariano. They receive annual training to review relevant Philippine laws and learn how to document and file a case for illegal activities. This component also entails lobbying with PAMB for management zones in the NSMNP.

Mabuwaya conducts capacity building by working with communities through consultations and workshops on land-use management and law enforcement, like management planning. With the growing interest in tourism, they have also conducted tour guiding training. This was to initiate the organization of tour guides and learn about best practices before promoting tourism in sanctuaries.

Philippine crocodile population re-enforcement and recovery necessitates protecting nests and nesting areas from predators and poachers. The eggs are gathered carefully, hatched, and raised in captivity for two years. Once the hatchlings develop into healthy [adults – kindly confirm], they are released back into the wild. This has become an anticipated event, participated by community members and school children, showing how locals are genuinely involved in conserving the biodiversity of the Park.

Biodiversity conservation with the Isabela oriole

The Isabela oriole (Oriolis isabellae) is a rare and exclusive, critically endangered bird. After a sighting in 1961, it was presumed extinct and rediscovered only in 1993 at the foothills of Sierra Madre. Merlijn van Weerd and Rob Hutchinson observed the Isabela oriole in 2003 at Ambabok, Disulap in San Mariano, with an estimated population of 1,000 – 2,499 individuals. It has been carefully studied since 2012, revealing that its significant threats were likely habitat loss from illegal logging and competition with other oriole species.

As of 2016, it was estimated that there were only around 70 – 400 left in the country. However, in the same year, the NSMNP adopted it as its flagship species. Aside from encouraging the research and conservation of the species, the Isabela oriole further brings attention to biodiversity conservation within the Park. This has contributed to the protection of other endangered and vulnerable species, such as the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), Philippine Eagle-Owl (Bubo philippensis), Golden-Crowned Flying Fox (Acerodon jubatus), Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas), Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta), Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), and Dugong (Dugong dugon).

Saving the Philippine Crocodile

The Mabuwaya Foundation located in Cabagan, Isabela, was established in 2003 to save one of the rarest species in the world: the endemic, freshwater Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis), as well as the saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) found in the same region It was on the brink of extinction in the 1990s, with negative ideas such as “corruption” associated with them.

Mabuwaya successfully applied its holistic conservation program. The local crocodile population grew from less than 20 to around 100. The wild population of crocodiles in the Park is still increasing. The program encompasses five components that empower communities and protect other critical species in the Park.

Communication, Education, and Public Awareness (CEPA) Campaigns focus on involving and organizing youth groups to educate them on the biodiversity of Sierra Madre. They work closely with the development communications students from Isabela State University (ISU) to conduct puppet shows, field visits, school lectures, and CEPA materials like posters, flyers, and a children’s book.

The research component mainly comprises biological, ecological, and telemetry studies of crocodiles to learn more about their characteristics, interactions within their environment, and where they gather in the NSMNP. Mabuwaya works with other institutions like ISU, the University of the Philippines Diliman, Los Baños, and Baguio, and the Netherlands University to produce even anthropological research within the Park.

Protection was born from the need to equip locals, including indigenous people, with the skills to participate effectively in community-based conservation. Mabuwaya’s COO, Marites Gatan-Balbas, and Director Merlijn van Weerd are training twelve sanctuary guards to manage the crocodile sanctuaries in San Mariano. They receive annual training to review relevant Philippine laws and learn how to document and file a case for illegal activities. This component also entails lobbying with PAMB for management zones in the NSMNP.

Mabuwaya conducts capacity building by working with communities through consultations and workshops on land-use management and law enforcement, like management planning. With the growing interest in tourism, they have also conducted tour guiding training. This was to initiate the organization of tour guides and learn about best practices before promoting tourism in sanctuaries.

Philippine crocodile population re-enforcement and recovery necessitates protecting nests and nesting areas from predators and poachers. The eggs are gathered carefully, hatched, and raised in captivity for two years. Once the hatchlings develop into healthy [adults – kindly confirm], they are released back into the wild. This has become an anticipated event, participated by community members and school children, showing how locals are genuinely involved in conserving the biodiversity of the Park.

Biodiversity conservation with the Isabela oriole

The Isabela oriole (Oriolis isabellae) is a rare and exclusive, critically endangered bird. After a sighting in 1961, it was presumed extinct and rediscovered only in 1993 at the foothills of Sierra Madre. Merlijn van Weerd and Rob Hutchinson observed the Isabela oriole in 2003 at Ambabok, Disulap in San Mariano, with an estimated population of 1,000 – 2,499 individuals. It has been carefully studied since 2012, revealing that its significant threats were likely habitat loss from illegal logging and competition with other oriole species.

As of 2016, it was estimated that there were only around 70 – 400 left in the country. However, in the same year, the NSMNP adopted it as its flagship species. Aside from encouraging the research and conservation of the species, the Isabela oriole further brings attention to biodiversity conservation within the Park. This has contributed to the protection of other endangered and vulnerable species, such as the Philippine Eagle (Pithecophaga jefferyi), Philippine Eagle-Owl (Bubo philippensis), Golden-Crowned Flying Fox (Acerodon jubatus), Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas), Loggerhead Turtle (Caretta caretta), Hawksbill Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), and Dugong (Dugong dugon).

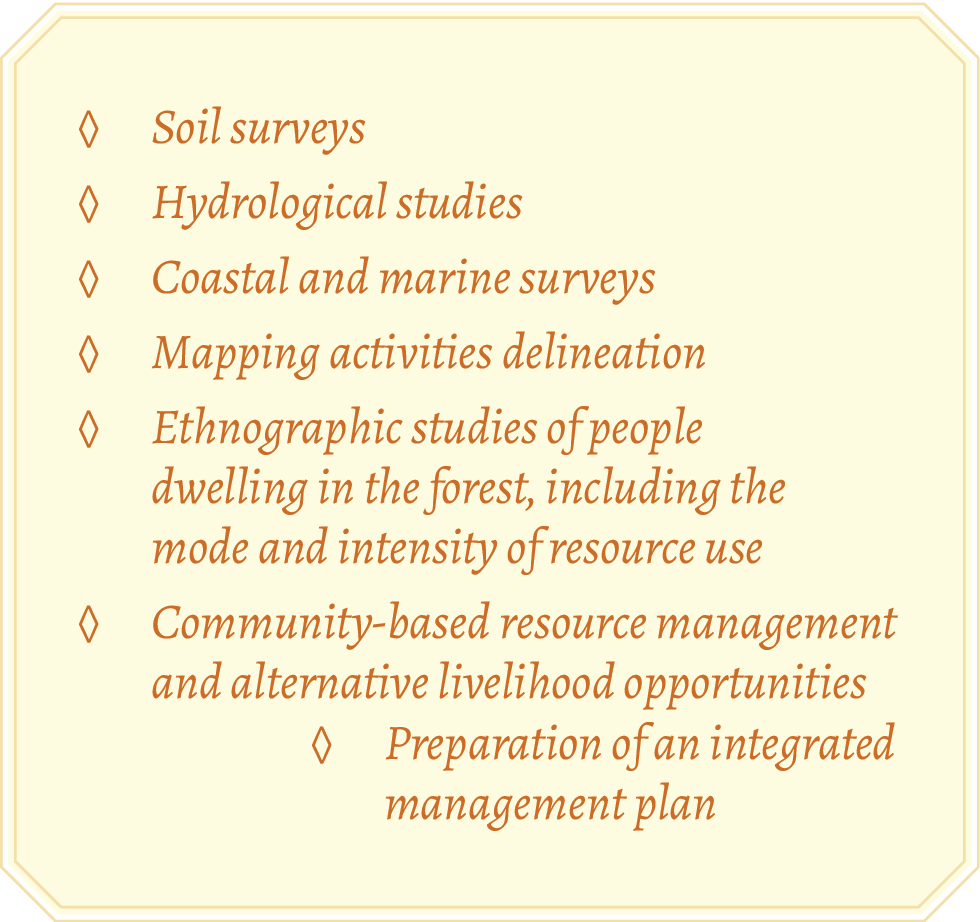

The NSMNP Conservation Project

The NSMNP Conservation Project (NSMNP-CP) began in 1996. It ended in October 2002, funded and initiated by the Dutch Government to sustain the natural resources of the Park by improving community-based protection and conservation activities while enhancing the quality of life of the local population. With the project’s success, it was followed by the NSMNP Conservation and Development Project (Phase 2) implemented by WWF Philippines.

An interview with Dr. Roberto Araño, the former Director of NSMNP-CP, revealed that facilitating the enactment of RA 9125, or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) Act of 2001, was among its milestones. This was a legal safeguard against those with vested interests, like logging and mining companies.

An interview with Dr. Roberto Araño, the former Director of NSMNP-CP, revealed that facilitating the enactment of RA 9125, or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) Act of 2001, was among its milestones. This was a legal safeguard against those with vested interests, like logging and mining companies.

This success can be attributed to the coordination between non-government organizations, academic institutions, local stakeholders, and collaborators – producing valuable information supporting the need for RA 9125. The Isabela State University, Leiden University, and Mabuwaya Foundation were among those who consistently and actively contributed to research in NSMNP. Some of these studies were presented at the Fourth Regional Conference on Environment and Development titled The Sierra Madre Mountain Range: Global Relevance, Local Realities.

Rigorous baseline studies and surveys were conducted to prepare the management plan for the Park, given the need for more literature and knowledge about the area. These studies provided insight into the primary issues within and around the Park and the potential ways to manage or prevent them. Plan International identified the following research components:

Dr. Araño commented during the interview that there is a lack of political will to implement conservation plans and strongly prohibit illegal activities despite opposition. In the 2014 study that he co-authored with Dr. Persoon, the conflicts and overlapping claims to land and forest resources were among the factors that limited the implementation of the Project. Aside from local disputes, those among government agencies such as the DENR-MGB, DENR-FMB, NCIP, and LGUs exacerbated zoning problems. This is most evident in the halted process of securing formal land claims for the Agta in the NSMNP.

Despite these challenges, there is much hope for the protection of the Park. According to the interview with Marites Gatan-Balbas and Merlijn van Weerd of the Mabuwaya Foundation, no species in the area have gone extinct. The current [2003] PAMB Chair also has a stronger political will to execute conservation efforts. In the future, the general public’s growing awareness of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range will hopefully push for stricter protection of the Park.

The NSMNP Conservation Project

The NSMNP Conservation Project (NSMNP-CP) began in 1996. It ended in October 2002, funded and initiated by the Dutch Government to sustain the natural resources of the Park by improving community-based protection and conservation activities while enhancing the quality of life of the local population. With the project’s success, it was followed by the NSMNP Conservation and Development Project (Phase 2) implemented by WWF Philippines.

An interview with Dr. Roberto Araño, the former Director of NSMNP-CP, revealed that facilitating the enactment of RA 9125, or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) Act of 2001, was among its milestones. This was a legal safeguard against those with vested interests, like logging and mining companies.

An interview with Dr. Roberto Araño, the former Director of NSMNP-CP, revealed that facilitating the enactment of RA 9125, or the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) Act of 2001, was among its milestones. This was a legal safeguard against those with vested interests, like logging and mining companies.

This success can be attributed to the coordination between non-government organizations, academic institutions, local stakeholders, and collaborators – producing valuable information supporting the need for RA 9125. The Isabela State University, Leiden University, and Mabuwaya Foundation were among those who consistently and actively contributed to research in NSMNP. Some of these studies were presented at the Fourth Regional Conference on Environment and Development titled The Sierra Madre Mountain Range: Global Relevance, Local Realities.

Rigorous baseline studies and surveys were conducted to prepare the management plan for the Park, given the need for more literature and knowledge about the area. These studies provided insight into the primary issues within and around the Park and the potential ways to manage or prevent them. Plan International identified the following research components:

Dr. Araño commented during the interview that there is a lack of political will to implement conservation plans and strongly prohibit illegal activities despite opposition. In the 2014 study that he co-authored with Dr. Persoon, the conflicts and overlapping claims to land and forest resources were among the factors that limited the implementation of the Project. Aside from local disputes, those among government agencies such as the DENR-MGB, DENR-FMB, NCIP, and LGUs exacerbated zoning problems. This is most evident in the halted process of securing formal land claims for the Agta in the NSMNP.

Despite these challenges, there is much hope for the protection of the Park. According to the interview with Marites Gatan-Balbas and Merlijn van Weerd of the Mabuwaya Foundation, no species in the area have gone extinct. The current [2003] PAMB Chair also has a stronger political will to execute conservation efforts. In the future, the general public’s growing awareness of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range will hopefully push for stricter protection of the Park.

The NSMNP Through the Years

The NSMNP Through the Years

Photos Of Wildlife in the

Northern Sierra

Madre

Natural Park

Help others appreciate the incredible biodiversity of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. If you have photos of animal or plant species that you’d like to share, you can upload them here. We’ll share verified photos on this page, and we’ll include your name as a photography credit. Contribute to citizen science by showing the world the wonders of our native species.

Photos Of Wildlife in the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park

Help others appreciate the incredible biodiversity of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. If you have photos of animal or plant species that you’d like to share, you can upload them here. We’ll share verified photos on this page, and we’ll include your name as a photography credit. Contribute to citizen science by showing the world the wonders of our native species.

Research on the

Northern Sierra Madre

Natural Park

Have you done research in the Park? We are looking for published works that we can feature on this platform, which will include a page filled with current findings and studies on the Park’s natural resources, wildlife, residents, conservation efforts, management, and more. Upload your research here so we can help it reach a wider audience.

Research on the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park

Have you done research in the Park? We are looking for published works that we can feature on this platform, which will include a page filled with current findings and studies on the Park’s natural resources, wildlife, residents, conservation efforts, management, and more. Upload your research here so we can help it reach a wider audience.

Conservation Actions for

the Northern Sierra

Madre Natural Park

Were you involved in any conservation or advocacy project within NSMNP? Share your completed or on-going work with us so we can feature it on the website.

Conservation Actions for the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park

Were you involved in any conservation or advocacy project within NSMNP? Share your completed or on-going work with us so we can feature it on the website.

Developed by Forest Foundation Philippines

Editorial and Design by Drink Sustainability Communications

Developed by Forest Foundation Philippines

Editorial and Design by Drink Sustainability Communications

References

Carandang, A.P. et al. (2013). Analysis of key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in the Philippines. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

Climate Adaptation Platform (2022, January 12). Impacts of super typhoons and climate change. PreventionWeb.

Congress of the Philippines (1992). Republic Act No. 7586: National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992. An Act Providing for the Establishment and Management of National Ingrated Protected Areas System, Defining Its Scope and Coverage, and for Other Purposes.

Congress of the Philippines (2001). Republic Act No. 9125: Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) Act of 2001. An Act Establishing the Northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range Within the Province of Isabela as a Protected Area and Its Peripheral Areas as Buffer Zones, Providing for Its Management and for Other Purposes.

Congress of the Philippines (2018). Republic Act No. 11038: Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018. An Act Declaring Protected Areas and Providing for Their Management, Amending for This Purpose Republic Act No. 7586, Otherwise Known as the “National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS) Act of 1992” and for Other Purposes.

Cruz, W. D., & Cruz, M. C. J. (1990). Population pressure and deforestation in the Philippines. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 7(2), 200–212.

Environmental Science for Social Change. Isabela Land Cover Assessment Project.

Forest Global Earth Observatory. (n.d.). The Palanan Forest Dynamics Plot. Smithsonian Institution.

Global Business Reports. (2013). Mining in the Philippines: Revisiting the rim.

Hagen, R.V. & Minter, T. (2020) Displacement in the name of development. How indigenous rights legislation fails to protect Philippine hunter-gatherers. Society & Natural Resources, 33(1), 65-82.

Ilagan, K. (2023, May 12). Timeline: Losing, saving Philippine forests. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

Israel, D. C. & Briones, R. M. (2012). Impacts of natural disasters on agriculture, food security, and natural resources and environment in the Philippines (PIDS Discussion Paper Series No. 2012-36).

Minter, T. (2010). The Agta of the Northern Sierra Madre. [Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University].

Minter, T., van der Ploeg, J., & Pedrablanca, M. et al. (2014). Limits to indigenous participation: The Agta and the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the Philippines. Human Ecolology, 42, 769–778.

Mabuwaya Foundation. (2018). The Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. Mabuwaya Foundation, Inc.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Kaingin. In Merriam-Webster: America’s Most Trusted Dictionary dictionary. Retrieved September 13, 2023

Ploeg, V.D., Bernardo, E.C., & Masipiqueña, A.B. (2003). The Sierra Madre Mountain Range : Global relevance, Local realities. Golden Press.

Pulhin, J. M., Catudio, M. L. R. O., & Pulhin-Yoshida, P. M. (2021). Forest Conservation in the Philippines: Linking people, forests, and policies. In A. La Viña, J. A. Canivel, & D. P. Reyes (Eds.), Forests in the Anthropocene: Perspectives from the Philippines (pp.12-67). Forest Foundation Philippines.

Racoma, B.A.B., David. C.P.C., Crisologo, I.A., & Bagtasa, G. (2016). The change in rainfall from tropical cyclones due to orographic effect of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range in Luzon, Philippines. Philippine Journal of Science, 145(4), 313-326.

Tan, J.M.L. (2000). The last great forest: Luzon’s Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. The Bookmark, Inc.

References for Threats to the Sierra Madre Natural:

Carandang, A.P. et al. (2013). Analysis of key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in the Philippines. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

Climate Adaptation Platform (2022, January 12). Impacts of super typhoons and climate change. PreventionWeb.

Cruz, W. D., & Cruz, M. C. J. (1990). Population pressure and deforestation in the Philippines. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 7(2), 200–212.

Environmental Science for Social Change. Isabela Land Cover Assessment Project. Isabela Land Cover Assessment – Institute of Environmental Science for Social Change

Forest Global Earth Observatory. (n.d.). The Palanan Forest Dynamics Plot. Smithsonian Institution.

Global Business Reports. (2013). Mining in the Philippines: Revisiting the rim.

Hagen, R.V. & Minter, T. (2020). Displacement in the name of development. How indigenous rights legislation fails to protect Philippine hunter-gatherers. Society & Natural Resources, 33(1), 65-82.

Ilagan, K. (2023, May 12). Timeline: Losing, saving Philippine forests. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

Israel, D. C. & Briones, R. M. (2012). Impacts of natural disasters on agriculture, food security, and natural resources and environment in the Philippines (PIDS Discussion Paper Series No. 2012-36).

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Kaingin. In dictionary. Retrieved September 13, 2023, from

Minter, T. (2010). The Agta of the Northern Sierra Madre. [Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University].

Minter, T., van der Ploeg, J., & Pedrablanca, M. et al. (2014). Limits to indigenous participation: The Agta and the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the Philippines. Human Ecolology, 42, 769–778.

Mabuwaya Foundation. (2018). The Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. Mabuwaya Foundation, Inc.

Ploeg, V.D., Bernardo, E.C., & Masipiqueña, A.B. (2003). The Sierra Madre Mountain Range : Global relevance, Local realities. Golden Press.

Pulhin, J. M., Catudio, M. L. R. O., & Pulhin-Yoshida, P. M. (2021). Forest Conservation in the Philippines: Linking people, forests, and policies. In A. La Viña, J. A. Canivel, & D. P. Reyes (Eds.), Forests in the Anthropocene: Perspectives from the Philippines (pp.12-67). Forest Foundation Philippines.

Racoma, B.A.B., David. C.P.C., Crisologo, I.A., & Bagtasa, G. (2016). The change in rainfall from tropical cyclones due to orographic effect of the Sierra Madre Mountain Range in Luzon, Philippines. Philippine Journal of Science, 145(4), 313-326.

Tan, J.M.L. (2000). The last great forest: Luzon’s Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. The Bookmark, Inc.

With interviews from the following:

Former Chairperson, Forest Foundation Philippines, Jose Ma. Lorenzo “Lory” Tan

Former Director of the NSMNP-Conservation and Development Project Roberto R. Araño, personal communication, August 22, 2023

NSMNP Protected Area Superintendent Nestor Lorenzo, personal communication, August 22, 2023

Mabuwaya Foundation COO Marites Gatan-Balbas, personal communication, August 24, 2023

Mabuwaya Foundation Director Merlijn Van Weerd, personal communication, August 24, 2023

Sources for Interactive Map:

Araño, R., & Persoon, G. (2014). Action Research For Community-Based Resource Management And Development: The Case of the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park Conservation Project, Northeastern Philippines. Research in tropical rain forests: Its challenges for the future.

Asian Species Action Partnership . (n.d.). Isabela OrioleOriolus isabellae.

Baleva, J. (n.d.). Road to Divilacan; Its promises and worries.

Chemonics International Inc. (2015). Vulnerability Assessment of Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park. Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program. Retrieved from

Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. (2001). The Philippine Hotspot.

Department of Environment and Natural Resources . (2016). Joint FMB-BMB Technical Bulletin NO. 2016-01.

Department of Public Works and Highways . (2020). dpwh.gov.ph.

Department of Public Works and Highways. (2021). Notice of Award – Construction of Ilagan-Divilacan Road, Isabela .

Dipudo Private Island Resort, Divilacan, Isabela . (2023). Waiting for the Road.

Domingo, Leander C.; The Manila Times. (2019). P1.6-B Isabela road to open soon.

GoodEarth Mining & Development Inc. (n.d.).

Hagen, R. V., & Minter, T. (2020). Displacement in the Name of Development. How Indigenous Rights Legislation Fails to Protect Philippine Hunter-Gatherers. Society & Natural Resources, 65-82.

Haribon Foundation . (2016). Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, The Country’s Biggest Natural Forest.

Isabela, P. G. (2014). Invitation to Bid for Ilagan-Divilacan Road Rehabilitation and Improvement Project.

Lagasca, C. (2012). Retrieved from Philippine Star.

Mabuwaya Foundation. (n.d.). Home.

Minter, T. (2010). The Agta of the Northern Sierra Madre. Livelihood strategies and resilience among Philippine hunter-gatherers.

Minter, T., Ploeg, J., Pedrablanca, M., Sunderland, T., & Persoon, G. A. (2014). Limits to Indigenous Participation: The Agta and the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the Philippines.

Nickel Asia Corporation (NAC). (n.d.). Dinapigue Mining Corporation.

Perez, G.J., et al. (2020). Reforestation and Deforestation in Northern Luzon, Philippines: Critical Issues as Observed from Space. Forests.

Philippine Information Agency. (2022). Divilacan will accept tourists soon.

Ploeg, J. van der, Bernardo, E. C., & Masipiqueña, A. B. (2003). The Sierra Madre Mountain Range: Global Relevance, Local Realities.

Ploeg,J., et al. (2011). Illegal Logging in the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the Philippines. Conservation and Society.

Province of Isabela . (n.d.). Invitation to Bid for Ilagan-Divilacan Road Rehabilitation Project.

Province of Isabela . (n.d.). Tourist Destinations.

Province of Isabela. (n.d.). Tourist Destinations.

Republic of the Philippines . (1992). National Integrated Protected Areas System Act 1992 (Republic Act No. 7586 of 1992).

Republic of the Philippines . (n.d.). Republic Act 11038 Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 2018.

Republic of the Philippines. (2000). Republic Act No. 9125. An Act establishing the Northern Sierra Madre Mountain Range within the province of Isabela as a protected area and its peripheral areas as buffer zones providing for its management and for other purposes.

Republic of the Philippines. (2001). Republic Act No. 9125 Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park (NSMNP) Act of 2001.

Rosario, Ben; Manila Bulletin Publishing Corp. (2018). Solon asks DPWH to summon contractor of failed Isabela road project.

Siytangco, AJ; Manila Buletin. (2018). P1.6-B Isabela road project overpriced to say the least – Rep. Dy.

Smithsonian . (n.d.). Palanan.

Tan, J. M. (2020). The Last Great Forest . The Bookmark, Inc.

United Nations Environment Program- LEAP. (2018). DENR Administrative Order No. 2018-21 on the Lawin Forest and Biodiversity Protection System as a National Strategy for Forest Biodiversity Protection in the Philippines.

UP Biology . (n.d.). Featured Research: The Palanan Forest Dynamics Plot.

USAID-BWISER Program. (2019). Transforming Forest and Biodiversity Protection in the Philippines Summary of Accomplishments 2012-2018.

Van der Ploeg, J., et al. (2008). Crocodile Rehabilitation, Observance and Conservation (CROC) project: the conservation of the critically endangered Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus mindorensis) in Northeast Luzon, the Philippines. Final report BP Conservation Program Consolidation Award. Mabuwaya Foundation. Cabagan.

Van der Ploeg, J., et al. (2016). Recognising Land Rights For Conservation? Tenure Reforms In The Northern Sierra Madre, The Philippines. Conservation and Society.

Photo Credits:

- Jose Ma. Lorenzo “Lory” Tan

- Mabuwaya Foundation